by Roslynn Beighton*

I spent much of 2016 working for a women’s rights group in Myanmar (Burma), which gave me the opportunity to learn about the human rights violations most of the country’s indigenous ethnic groups have been facing for generations, but particularly since the military coup of 1962. Since returning to the UK I have noticed an increase in news stories on the persecution of the Rohingya Muslim minority. International attention has grown after renewed waves of violence and the UN’s investigation into Rohingya refugees camps in Bangladesh.

During my time in Myanmar, I lived in Karenni (or Kayah) state working with the Karenni National Women’s Organisation. Stories about the plight of the Rohingya had surfaced significantly during the 2015 election and I was curious to understand local perspectives of the issue. My efforts to speak with my Karenni students, NGO workers and political party leaders in Myanmar about the Rohingya were met with mixed reactions. Many averted their eyes and refused to talk about their views in detail. My questions addressing the sheer injustice of the military crackdown were often met with resistance and some even defended the attacks. For example, someone I met through my workplace, a Buddhist national from Arakan (Rakhine) state was anxious that I should understand the problem from a Buddhist perspective, claiming that the Rohingya have also burned down the villages of ‘his people’ and showing frustration at international media ‘taking sides’ with the Muslim minority.

I am aware that my discussions with the individuals I spent time with do not necessarily represent the views of a whole group or state. Nevertheless, I felt uncomfortable at the lack of outrage, especially on the suffering of many women and children.

State apathy on the suffering of Rohingya

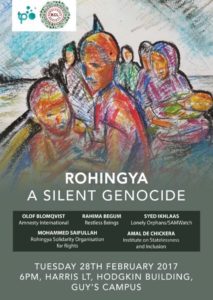

I attended a talk titled ‘Rohingya: A Silent Genocide’ at the King’s College last month. It was organised by Ayesha Tarannum, a third year university student and member of the KCL Bangladesh society who felt compelled to highlight what she sees as a consistent silence from governments on the issue. She invited guest speakers from various institutions and NGOs to provide insights into the conflict and draw on their personal experiences of working with the Rohingya community. The lecture room was filled with students, charity and NGO workers, politicians, Burmese citizens and a member of the Rohingya community who had sought asylum in the UK in the 1990s. After some excellent speeches from a panel of speakers from Myanmar, Bangladesh and the UK, we all seemed to come to the sad conclusion that unless governments acknowledge that this is a genocide and are strongly lobbied, the Rohingya population will continue to be wiped out.

The first speaker, Amal de Chikera, co-founder of the Institute of Statelessness and Inclusion, explained how Myanmar’s 1982 citizenship law rendered the Rohingya stateless and how their consideration as ‘resident foreigners’ has set the foundation for rampant human rights violations by the Burmese military. The Rohingya bear restrictions on their freedom of movement, discriminatory limitations on marriage, employment and access to education, arbitrary arrest and confiscation of property, and have even been subjected to a hugely discriminatory and cruel two child policy applied to them in an attempt to regulate the population, which violates international human rights protections and endangers women’s physical and mental health. In 2015, revocation of all Temporary Registration Cards left many Rohingya without any form of identity document so they became effectively barred from voting.

De Chikera explained how Rohingya communities outside of Myanmar continue to face a tenuous existence in countries such as Bangladesh, Indonesia and Malaysia, where tens of thousands have fled during an alarming rise in religious intolerance which has forced them from their ancestral state of Arakan in the north-west of Myanmar. Most of their host countries do not recognise asylum seekers and have not signed the U.N. Refugee Convention. Living as ‘urban refugees’ in shantytowns in Malaysia and Indonesia which are at least more ‘Muslim-friendly,’ is a better option than being targeted by extremist religious groups such as the 969 movement led by Buddhist monk Wirathu.

The Rohingya’s desperation has been particularly highlighted by international media outlets in recent years, primarily after the 2012 Arakan state riots, the 2015 refugee crisis and 2016 military crackdown. In 2015, over 8,000 refugees were stranded at sea after the Malaysian and Indonesian governments refused to allow the boats to dock and overcrowded vessels were abandoned by people traffickers. In winter 2016, 96,000 are estimated to have fled after the military’s ferocious response to attacks on border guard posts by several hundred Muslim men. The reaction was described as ‘grossly disproportionate’ by signatories of an open letter to the UN security council who were Nobel Laureates emphasising the humanitarian crisis and warning of the potential for genocide.

A report by a team of UN human rights investigators released in February 2017 documents mass gang-rape, killings involving mutilation, brutal beatings, disappearances, psychological torture, forced labour, as well as the denial of rights to health and education, lack of emergency medical care and the burning of dwellings, some with families still inside their homes – evidenced by high resolution satellite imagery from Human Rights Watch.

Yet while reporting on the Rohingya humanitarian crisis is increasing, the Burmese government denies the atrocities committed and de facto leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, has failed to condemn the atrocities endured by arguably one of the most persecuted groups on earth. Some speakers from the panel at the lecture went so far as to term ‘the lady’ a ‘despotic leader’ and perhaps this claim is not unjust considering the gap between her rhetoric for indigenous ethnic minorities and the reality of deep oppression experienced by millions in the country.

Other governments have refused to acknowledge the issue, further compounding the problem of statelessness. The Convention on the Rights of the Child guarantees every child the ‘right to acquire a nationality’ under article 7, and also obligates state parties to implement this right ‘in particular where the child would otherwise be stateless.’ De Chikera expressed that as long as state apathy on the Rohingya exodus continues, the rest of the world is sending a clear message to the Myanmar government: they can get away with this ‘genocide.’

Inspiring grassroots movements do however offer hope. The organisation Restless Beings is one example. Mabrur Ahmed, its director and founder, seemed to inspire the audience with the support he has been offering to the Rohingya and other marginalised groups around the world for the past decade. Similarly, Ayesha Tarannum’s passion and energy in organising the lecture portrayed her desire to widen visibility of the issue and inspire others to join the cause – no matter your skill set or experiences, anyone’s support is valued in an organisation such as Restless Beings.

Need for action

During the lecture, the point that came up throughout was the need for government action and commitment to decry the genocide and offer refuge and citizenship to those fleeing to countries such as Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. A global voice is needed to pressure governments and other states to actively bring an end to this situation and criticize the Myanmar government for its justification of the repression as a safeguard against fundamentalism.

‘A Silent Genocide’ ended with a chilling story from Syed Ikhlaas, head of the charity Lonely Orphans and member of South Asian Minority Watch. After showing some graphic and hard-hitting footage of the circumstances witnessed by journalists, aid workers and members of Rohingya communities themselves, he told of a young Rohingya woman who had been gang-raped by Burmese soldiers and found by aid workers in a refugee camp in Bangladesh. They saw that she had had a miscarriage and been unable to clean herself for days. The message I received was that the Rohingya had been completely stripped of their dignity and innate right to be valued and receive ethical treatment. The frustration and grief in the room was tangible.

The persecution of the Rohingya is not just a humanitarian crisis but a war on a people whose very existence is being denied. They have been referred to as ‘fleas’ and ‘pests’ which furthers the process of their dehumanization. Perhaps it is easy to become desensitized by the saturation of images of war and terror around the world but I think the harrowing stories that are continually emerging are fuelling a movement calling out the genocidal nature of the Rohingya experience. We must always remember the humanity of such persecuted groups and individuals. We need more people like Amal de Chikera, Mabrur Ahmed and Syed Ikhlaas to organise collective outrage and pressure governments by lobbying to avoid the looming forecast of another Rwanda. Collectively mobilising against atrocities committed against ethnic minorities is the only way to end the ongoing discrimination, displacement and systematic removal of the Rohingya by the Myanmar government and other states.

A big thank-you to all the guest speakers and especially Ayesha Tarannum for organising the event and bringing together a community to speak out against the persecution of the Rohingya.

* Roslynn Beighton is an MA student in Understanding and Securing Human Rights at the School of Advanced Study, University of London. Roslynn is currently a Communications Intern at the MRG and previously worked for a women’s rights group in Myanmar.