By Fumiya Nagai*

It has been 10 years since the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was adopted at the UN General Assembly on 13 September 2007. The adoption of the UNDRIP was one of the most important achievements in the indigenous peoples’ rights movement at the global level. As this year is the 10th anniversary of the UNDRIP, its implementation is being reviewed to discuss the progress and challenges it presents at various places including the Human Rights Consortium at the School of Advanced Study, University of London. In this article, I will discuss the situation of the indigenous peoples’ rights protection mainly for the Ainu people in Japan, particularly taking a look at the current Ainu policy and the recent development of the forest certification mechanism.

To understand and consider contemporary circumstances of indigenous peoples who have struggled for their rights for a long time, the history of the remaining colonialism would not be negligible. It is quite important to raise the fact that a significant part of indigenous peoples’ identity derives from colonial rule such as mass-killings, genocide, marginalisation, assimilation, resettlement as well as cultural destruction. Through the indigenous rights movement, they have fought for the recognition of being “peoples” who hold the right to self-determination, requiring the protection and benefits of international law. In this regard, while independent statehood is not something indigenous peoples have pursued, the establishment and implementation of the UNDRIP could be regarded as an extension of the process of decolonisation.

Traditional Ainu Settlement Areas and Ainu Population in Hokkaido (2013 Survey on Ainu Living Condition)

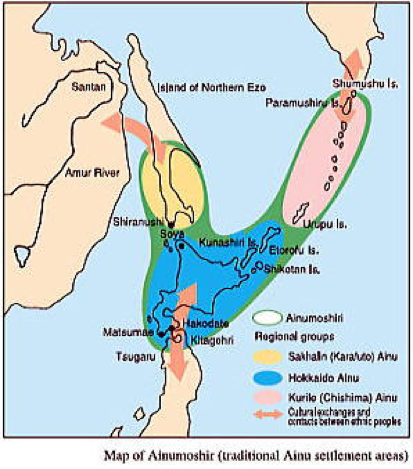

In my country of Japan, one of the indigenous peoples, the Ainu people, have also suffered from colonialism. Originally, they inhabited Hokkaido, the northern island of Japan, and the far-eastern region of Russia. Currently, according to the latest survey on the Ainu living condition in Hokkaido in 2013, although it is not comprehensive, the number of the Ainu people was at least 16,786. It was soon after the Meiji Restoration and modern nation-state building in the 1860s that the Government of Japan began having direct control over Ainu traditional land by renaming it Hokkaido. Based on the justification of the doctrine of terra nullius, the Government dispossessed the Ainu of their lands and sovereignty, and their cultural manners and customs were prohibited or strictly limited with assimilative policies and legislations, notably the establishment of the “Former Native Protection Act” in 1899. Throughout colonial rule, the Ainu people were also regarded as a “dying race”, and most notoriously, Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone referred to Japan as an ethnically “homogeneous nation” in 1986. His statement became one of the factors that triggered the Ainu representatives to participate in the international indigenous network, which started in 1987.

Traditional Ainu Settlement Areas and Ainu Population in Hokkaido (2013 Survey on Ainu Living Condition)

However, until 2008, a year after the adoption of the UNDRIP, the Government had still failed to recognise the Ainu as an indigenous people. In addition, while the Government also began working on Ainu policy having recognised them as a people, it has been based on the “Japan-Specific Indigenous Policy” view. According to this view, sovereignty status and related rights such as the right to self-determination does not fit in the context of Japan, and indigenous rights outlined in the UNDRIP has been referred to only if they are relevant. For example, collective rights that consist of the major part of the rights of indigenous peoples are not necessarily protected because the Japanese Constitution is based on individualism. Moreover, cultural aspects are prioritised as they easily coincide with the benefits of the majority population in Japan. In this regard, the current Ainu policy has been moving away from what indigenous peoples including the Ainu have pursued through their rights movement and the implementation of the UNDRIP for decolonisation.

In this situation, private sectors’ voluntary approaches have also been increasingly paid attention to. One of the most notable developments in recent years is forest certification, and the amendment of the Principles and Criteria (P&C) of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) in 2012. FSC is an international non-governmental organisation that runs the global forest certification mechanism, which certifies whether forests are environmentally responsible, socially beneficial, and economically viable. The P&C are a set of rules for it, and one of the 10 Principles (Principle 3) has been on indigenous rights, recognising indigenous peoples as rights holders including the Ainu people.

Before the 2012 revision, under the FSC scheme the primary normative reference for indigenous rights was ILO Convention 169. However, the Government of Japan has not ratified it, so indigenous rights protection under the scheme is considered not necessarily effective in Japan. On the other hand, the new standards have become stricter, and importantly, the UNDRIP has been included as a normative reference. As the Government of Japan voted in favor for the adoption of the UNDRIP and has recognised the Ainu as an indigenous people, FSC Japan has also acknowledged that Principle 3 would be applied to the Ainu people and forests in Hokkaido in 2013. In this regard, compared with the Governmental policy, the FSC scheme seems to go a step further for the implementation of the UNDRIP, and the revision of the FSC P&C is quite implicative for the Ainu rights protection.

Nonetheless, the situation of FSC certification does not warrant optimism as it still faces some challenges. One of them is for example, that the forest certification is a voluntary and market-driven mechanism. Although the price premium is recognised for the certified products in the Japanese market, it is not considered high. In this sense, the mechanism might not be influential enough to change forest practices, although certificates could be suspended depending on the scale and number of non-conformities against the standards. Also, not all of the forests in Hokkaido are FSC-certified. In addition, the certification process is not completely independent from local or national laws and policy. The lack of domestic laws on the Ainu rights might make it unclear, for instance, on which sites the Ainu hold their indigenous rights. Similarly, as there is no official representative or decision-making institutions consented among the Ainu people, who the Free, Prior and Informed Consent should be obtained from might also be ambiguous.

One of the notable relationships between forest managers and the Ainu is found in relation to the Saru Forest in Biratori, Hokkaido, which is owned by the Mitsui Bussan, a general trading company in Japan. In 2010, along the P&C revision process, the agreements on the Saru Forest were concluded among the Biratori Ainu Association, the municipality of Biratori and the Mitsui Bussan. In the agreements, it is acknowledged that some plants and trees that are important for the Ainu culture are nurtured in the forest, and the Ainu people can use the resources when necessary for their cultural activities. However, the focus of the agreements is on preservation and promotion of the culture, but not on their rights protection. In other words, it is failed to discuss the rights of indigenous peoples for the Ainu in relation to the forest. For example, the agreements do not necessarily acknowledge that the Ainu people have the right to manage or freely access the forest. Nonetheless, these agreements are considered as one of the models for the relationships between the Ainu and forest managers in Hokkaido under FSC certification. In this sense, there still remains room that the protection of indigenous rights for the Ainu through forest certification could be dodged as well.

Considering these concerns and challenges, although it might be difficult to completely exclude the possibility that forest certification is appropriated to make forest managers socially acceptable, for the effective work of the mechanism, it is clearly important that the Governmental policy changes its current direction and takes a step to implement the rights of indigenous peoples for the Ainu. Furthermore, another significant point might be the quality of auditors because they inspect forest practices on-site and decide whether the certificate is given or not. However, in general, auditors of forest certification are professional in forestry and not in indigenous peoples’ rights, and the cost of fostering and training new auditors is high. Due to this, experts on indigenous peoples’ rights might be included into an audit team as a technical expert, or some human rights activists have begun working on providing programmes for auditors to learn human rights and the rights of indigenous peoples. However, considering the balance between the cost for and the quality of the certification, it might not necessarily be easy to achieve either. In this sense, while the recent development of the FSC scheme is quite suggestive in Japan, further efforts would still be necessary in cooperation with the Ainu.

As seen in the case of Japan above, the situations of the implementation of indigenous rights have changed for a decade since the adoption of the UNDRIP in 2007. While various challenges still remain, there have been some implicative developments as well, including the FSC forest certification. Welcoming the 10th anniversary of the UNDRIP, it is sincerely hoped that indigenous rights would be further promoted hereafter in Japan as well as in the globe.

* Fumiya Nagai is an MA student in Understanding and Securing Human Rights at the School of Advanced Study, University of London.